It’s one of engineering’s great anti-climaxes: no swelling music, no heroic speech—just three unglamorous syllables uttered on an open loop that turned chaos into “carry on.”

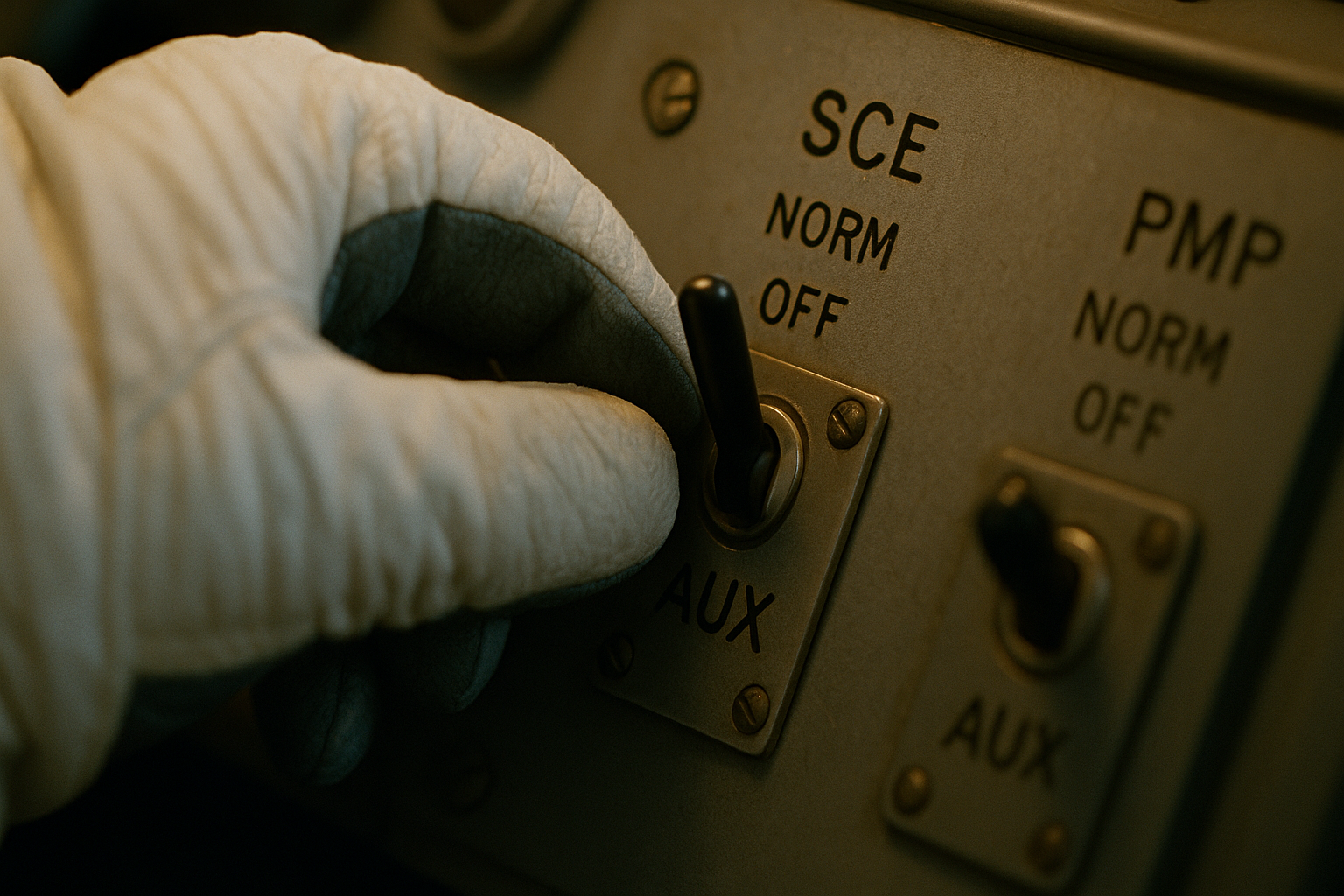

Scene: November 14, 1969. Apollo 12 climbs into a gloomy Florida sky. Thirty-six seconds after liftoff: zap. Consoles in Mission Control fill with numeric gibberish. The crew’s caution panel lights up. Sixteen seconds later: zap again. A young controller leans into the Flight loop with the least cinematic line in space history: “Try SCE to Aux.” Commander Pete Conrad: “What the hell is that?” Lunar Module Pilot Alan Bean, who actually knows where the obscure toggle lives, flips it. Telemetry snaps back. The mission continues.

What makes this story irresistible—and genuinely useful for DevOps—is that it isn’t a miracle. It’s a diagnostic story, an architecture story, and a people story about how deep system knowledge and a boring fallback beat drama every time.

What “SCE to AUX” actually means

SCE is the Signal Conditioning Electronics—the box that powers selected sensors and converts messy analog signals into standardized data for recording and downlink. The lightning-induced power sag upset SCE’s primary supply, so Mission Control saw garbage. Flipping the SCE switch to AUX selected the unit’s redundant internal supply; as soon as SCE had clean power again, the downlinked numbers stopped speaking in tongues. In other words, the data path—not the rocket—was “sick,” and a tiny, well-placed bypass restored truth.

Two details worth savoring:

- Where the switch lived. On the Command Module’s Panel 3, within Bean’s reach, sat a three-position SCE power switch—normally left at NORMAL for the primary supply; AUX selected the backup. It was labeled, documented, and physically reachable under g-load.

- Fix observability first. Restoring SCE didn’t heal everything; it restored telemetry, giving controllers the confidence and visibility to work subsequent resets (fuel cells back on line, guidance sanity checks, etc.). You cannot repair what you cannot see.

The minute-by-minute that made the legend

- T + 36.5 s: First lightning strike. Fuel cells drop off the buses; Mission Control data turns to confetti. “What the hell was that?” comes from the middle seat. oai_citation:4‡NASA

- T + 52 s: Second strike. The inertial platform tumbles; the commander’s attitude ball goes disco. The backup attitude path (GDC via BMAGs) still reads sane—a crucial hint that the Saturn V’s separate Instrument Unit is flying the stack just fine. oai_citation:5‡NASA

- T + ~1:39: EECOM John Aaron recognizes the glitch pattern from a past test and calls it: “SCE to AUX.” CAPCOM Gerald Carr relays; Bean flips; the numbers clean up; controllers proceed with methodical resets.

(A post-mission outcome: launch weather rules were tightened; NASA stopped launching into cloud decks with nearby lightning risk—knowledge written in lightning.)

Why John Aaron could say it in six syllables

Aaron wasn’t lucky; he was curious. In an earlier pad test he’d chased a similar “squirrelly numbers” signature to an SCE power upset. He filed the pattern away. When Apollo 12’s data went off-alphabet, he cut through the alarm cascade with a crisp, actionable sentence. Flight Director Gerry Griffin later recalled how obscure that switch was to most of the room—and how Bean’s muscle memory plus Aaron’s pattern recall saved the day.

The unromantic moral: postmortems and odd test artifacts are gold—if you study, reproduce, and remember them.

“Steely-eyed missile man,” decoded

The culture took notice. Aaron’s calm, exact call turned him into the archetype of the steely-eyed missile man—the person you want in the hot seat when the graph goes plaid. The exact origin of the phrase is murky, but Apollo era usage cemented it as the highest compliment for decisive, correct action under pressure.

The engineering behind the comedy

- Independent fallbacks. The Saturn V’s Instrument Unit—physically separate from the spacecraft—guided ascent. The Command Module’s backup attitude path (GDC/BMAG) was separate from the main IMU. The big rocket never cared about the spacecraft’s brief chaos. That’s segregation of concerns, in hardware.

- Human-centered failover. An obscure but documented toggle let a human select a redundant power rail without a reboot dance. That diagnostic path turned mystery into procedure.

- Observability as first responder. The first fix wasn’t the lightning; it was the eyes. Once telemetry was sane, the room could make correct calls about power and guidance.

The DevOps guide to your own “SCE to AUX”

You will not be asked to land near Surveyor 3, but you will be paged at 03:17 by a system that—because of a footnote in a vendor changelog—just ate its own telemetry. Here’s how to have your own boring, beautiful save.

1) Design a boring bypass for the day the numbers go weird

- Provide a low-ceremony switch (feature flag, CLI subcommand, or dashboard button) that restores observability when collectors/pipelines face-plant—e.g., a “direct health probe” that bypasses the normal bus and publishes to a side channel (AUX).

- Make it obvious and reachable. “Run

ops aux-telemetry enable” beats three SSH hops and tribal lore. - Document signatures. For every incident, keep two screenshots: good state and SCE-sick state. Train for recognition, not just rote steps. (That’s the John Aaron move.)

2) Separate guidance from telemetry

- Don’t tie control loops to pretty dashboards. If Prometheus dies, autoscaling shouldn’t. Keep control planes independent from observability stacks—the way the Saturn V flew via its own Instrument Unit while the spacecraft’s data went sideways.

- Maintain a stripped-down GDC path: a minimal, low-latency signal path surfacing only the few KPIs you need to judge stability (queue depth, error rate, p95 latency) using storage/transport different from your main metrics pipeline.

3) Train the right person to flick the right switch

- Rotate engineers through “obscure toggles.” Bean knew the SCE switch location because he’d practiced it. Run drills where someone must recover observability from memory, under time pressure.

- Drill sentence discipline. During an incident: short, specific imperatives—“Set ingest to AUX,” “Disable shard 7,” “Pin build to 2.3.1.” Poetry is for postmortems.

4) Make lightning boring

- Chaos-test your observability. We all chaos-monkey services; almost nobody chaos-monkeys telemetry. Simulate partial metrics blackouts, tag corruption, time skew, dropped exemplars. Score not just fix time but recognition time: how fast does someone call the scenario and flip the bypass?

- Gate launches on weather. Your “weather” might be deploy risk: third-party outage, hot partition, Black Friday traffic. If the clouds look angry, don’t light the candle. NASA learned that one hard.

5) Write runbooks like labels on physical switches

- Title with the action: “Restore Observability via AUX Path.”

- First line: When to use (signature). Second: one-liner to execute. Third: rollback.

- Put lore below the fold. If your runbook reads like a novel, nobody will use it when their hair’s on fire.

6) Institutionalize curiosity

- Reward the engineer who files the “weird numbers” ticket even when the bug won’t reproduce. Snapshot patterns and tag them with humans’ names—“Laura’s 2 a.m. Kafka fan-out”. That’s how you grow steely-eyed folks.

A closing riff (with Moon dust)

The best part of “SCE to AUX” is how plain it is. A controller murmurs a sentence. An astronaut flips a miniature seesaw. The giant rocket keeps flying. Mission Control exhales.

That’s the point. Engineering wins when drama loses.

When your next launch goes numerically sideways, do what Apollo 12 did: restore truth first, then act. Build the AUX path while you’re calm. Label it like something a gloved hand can find under 3.9 g. Drill it until the sentence you need is about six syllables long.

And when it works, don’t ruin the moment with adjectives. Lean toward the mic and say the line.